Facilitating Nigeria’s economic growth through rail and water transport

In December last year, the Financial Times reported that it cost almost the same to ship a container from China to Nigeria and to truck it to the warehouses in Lagos. According to the report, it cost more than $4,000 to truck a container 20km to the Nigerian mainland, almost as much as it costs to ship goods 12,000 nautical miles from China to Lagos. The perennial congestion, the report explained, cost the country $55m daily in lost economic activity and was largely caused by ageing infrastructure; poor rail transport that has forced 90 percent of freight traffic to the roads; and an almost complete lack of automation at the ports.

In January 2021, one month after the report, the Nigerian Ports Authority in a bid to digitalise and decongest port operations, announced the launch of the Eto app, an electronic truck call-up system that would manage the schedule, entry & exit of all trucks into the ports. The new system has although processed over 100 thousand trucks and registered over 5,700 stakeholders (transporters and transport companies) three months after its launch according to the app developer, Trucks Transit Parks (TTP) Limited, it is far from being successful due to the refusal of the petroleum tanker drivers and farm tank owners to key into the system. In a joint press statement released earlier this month, the NPA and Lagos State Government promised to commence engagements with the petroleum tanker drivers (with over 30 percent share of port-related traffic), tank farm owners and the NUPENG Union to address their concerns and integrate them into the new digital system.

While this is good to decongest the ports, the fact remains that 9 out of 10 containers are transported by road across the country. This is in sharp contrast to how the colonial administration moved goods in the early 20th century Nigeria. It was in the interests of the colonial administration to ensure that goods were moved in a cost-effective manner to the ports for exports so as to be competitive with those from other climes. Therefore, they built the railroads to link produce to the seaports for export. In essence, low value products were transported using rail, a low cost transport system.

The economic boost of colonial rail and water transport development

In the 1900-1901 Colonial Report of Northern Nigeria, the High Commissioner reckoned that the vast area of Nigeria could not be commercially developed except by railways and so they got to work. The construction of what is presently known as Nigerian major rail lines began with the Western Line in 1898 with the laying of a 34-km railroad from Iddo (Lagos) to Otta (Ogun) and then finally linking it with Jebba (Kwara) in 1909. The Eastern Line began in Port Harcourt in 1913 when the colonial administration discovered coal at Udi (near Enugu) in commercial quantity and also subsequently discovered Port Harcourt as a suitable harbour for coal export. The line stretched from Port Harcourt and reached Enugu in 1916. By 1930, the lines had linked the south up to the extreme North-East and North-West upcountry. In 1964, an extension of the Borno rail was built to link Kuru to Maiduguri. That brought the major functional stretch of single-track railroad in Nigeria to a total of 3,505 km.

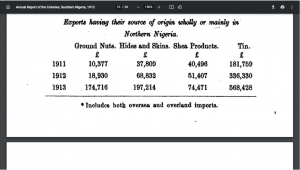

Apart from administrative ease, the major purpose for which the colonial administration built the rail lines was to transport agricultural goods and raw materials or natural resources across to the country’s ports for exports cheaply, efficiently and productively. And as they built, the volume and value of the colonies’ exports ballooned. For example, the worth of northern Nigeria’s agricultural exports spiked by about 150 percent just a year after the region was linked by rail, according to the Colonial Reports of 1913 which stated that “…this result being attributable to the improved transport facilities afforded by the railway to Kano, and in an almost equal degree to the larger output on the tin fields.” Furthermore, the value of Ground Nuts exports jumped from £10,377 in 1911 to £174,716 in 1913; £37,809 to £197,214 for Hides and Skins; £181,759 to £568,428 for Tins, among others. In the 1938 report, the colonial administration made £1,508,012 in net profit from railway services: total revenue was £2,834,967 while the total expenditure for the calendar year was £1,326,955.

Source: 1913 Annual Colonial Report, Southern Nigeria

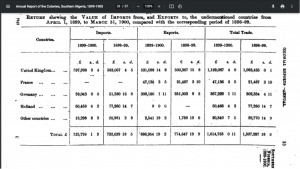

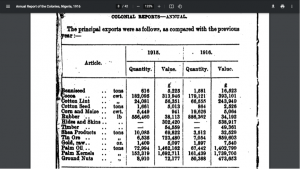

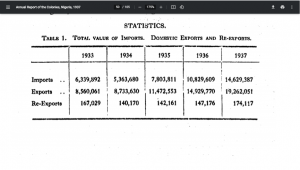

Comparing the worth of colonial exports between 1900 when the railway architecture was just being built; 1916 when the Western Line had passed Kwara from Lagos and the Eastern Line had reached Enugu from Port Harcourt and; in 1937 when most of the railroads had been built also shows the significance of deploying such an extensive yet cost-effective means of transportation across the country. The reports of these years revealed that the total value of exports in 1900 was £889 thousand, jumping to over £6 million in 1916 and then spiking to over £19 million in 1937.

Source: 1900 Annual Report of Colonies, Southern Nigeria.

Source: 1916 Annual Colonial Report, Nigeria.

Source: 1937 Annual Colonial Report

Before the construction of railroads across the country, the colonial administration majorly travelled through the waterways into the hinterlands and ferried agricultural produce and raw materials across the country and to the ports for export. When they began to build the railways, they transported the materials via the waterways. Therefore, water transport was an integral part of the political and economic administration of the British colonialists. In the 1900 Annual Colonial Report on Northern Nigeria for example, the High Commissioner, while arguing for the need to construct more than one rail line for the country, said “the Lagos railway will, beyond doubt, benefit Lagos, but since Northern Nigeria has the waterway of the Niger for the export of its produce, and since water carriage is cheaper than railage, it is not clear what benefit to its trade the Lagos railway will confer. Every yard, however, of a railway from the Niger to Kano would, by superseding the present caravan transport, tend greatly to promote the development of trade.”

In Southern Nigeria, water transport remained a viable and efficient means of cross-country movement of goods and services. In 1904, the vessels utilized for transhipping cargoes from the ports in Lagos to Forcados in Delta, through the colonial inland waterways Branch Service increased to 448 from 298 in 1902. In the 1913 Annual Report on the Colonies, Southern Nigeria, the Lagos-Siluko-Sapele marine services transported more passengers and goods than it did the previous year despite the suspension of their operations for three months because of yellow fever outbreak. The cargo traffic increased from 148 tonnes to 1,380 tonnes. By 1938, it had become a routine. That year’s report put it this way, “Marine Colliers transported Udi Coal from Port Harcourt to Lagos as usual, and mails were regularly carried between Lagos and Sapele.”

In 1955, the inland waterway cargo traffic had reached about 150,000 tons, traversing about 10 million ton-miles. The 47-mile Lagos-Epe section had the heaviest traffic, amounting to approximately 80,000 tons, according to a 1955 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development report (now The World Bank).

For the colonial administration, connectivity was principally to facilitate trade. This is not surprising since it earned a lot of duties from export of commodities. The export produce (agricultural products such as cocoa, palm oil and groundnuts) were low value products. To ensure that they are competitive compared to those available in other territories, transport costs had to be low. Essentially, low value agricultural products were transported by rail, a cheap transport mode and waterways where this was available.

Railway lines were built to connect towns with significant agricultural production to the ports where the products were exported. Of course, passenger trains were provided on the rails too but the transport of cargoes was prioritised.

And the rail and water transport infrastructure deteriorated

Since Independence in 1960, railway lines and waterways have fallen into disuse. Instead, goods are transported by road. Today, 90 percent of total freight movement is done by road, which itself is generally in a bad state – only 30 percent of Nigeria’s road network is paved. Much of the annual budgetary allocation to transport has always been on roads with little or no attention given to waterways and railways. Furthermore, much of the products of industrial estates and cities such as Aba, which has several factories, are shipped by road instead of rail and waterways, thereby increasing the cost of the products significantly.

The freight delays caused by the bad state of the roads and the road access charges paid at several check points on the route increases transport costs further. As our report on Connectivity and Productivity in Lagos megacity shows, poor connectivity leads to increased transport costs and longer time to market. These make companies uncompetitive.

It is an economic mismatch to deploy the most expensive means to transport low value products. A 2018 study by the Rail India Technical and Economic Service (RITES), for instance, revealed that one litre of fuel can move 24 tonnes through one kilometre on road, 95 kilometres on rail and 215 kilometres on inland water transport. Developing railroads and waterways, is critical if Nigerian businesses are to be competitive.

There have been recent efforts to rehabilitate and modernise the country’s railroads. In 2006, the Federal Government unveiled the Lagos-Kano standard-gauge modernisation project, which was awarded to CCECC for $8.3 billion. The project didn’t take off due to funding challenges. Former President Jonathan then rehabilitated and reopened the Lagos-Kano narrow-gauge line. But the fact that it was still a narrow-gauge line made it less desirable for fast and efficient passenger and freight transportation. Navigating the route at an average speed of 35 km per hour, it takes trains about 33 hours to complete the 1126-km journey which would have otherwise be completed in six hours by a speed train that travels up to 200 km per hour.

Our analysis of rail transport data from the National Bureau Statistics, which dates back to 2011 when the rail infrastructure started getting some attention from the Federal Government, showed that the rail roads have begun to see some activity but there is still a long way to go. Cargo traffic and revenues, which are critical to actualising the economic transformation potential of the rail transport system, still remain low. The volume of cargoes transported each year has not reached 2011 numbers (over 341 thousand tonnes), fluctuating from as high as 328 thousand tonnes in 2018 when the freight share of total revenue was only 20 percent to as low as 87 thousand tonnes in 2020. In 2019, NRC earned the most revenue (N2.776 billion). However, only 13 percent (about N363 million) came from cargo traffic. This is by far dwarfed by South Africa’s revenues from its railway. According to the Department of Statistics South Africa, the country’s rail lines transported about 175 million passengers in 2019 (only about 3 million in Nigeria) and moved over $3 billion worth of cargoes (only about $1 million in Nigeria).

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th Century, the colonial administration used the waterways extensively. Barges carried the construction materials for the railway along the waterways. They found that Nigeria has 3,800 kilometres of navigable waterways. Today, they are hardly used. Yet, an inland water infrastructure could help decongest the ports and reduce transport costs significantly.

What is being done?

The Financial Times report also noted that the Lagos port’s capacity has not increased since 1997, even as Lagos’s population has roughly tripled. Yet, it is the busiest port in the country. Our report on Connectivity and Productivity in Lagos Megacity showed that congestion costs micro, small and medium sized businesses between N600,053.90 and N5,400,478.20; N4,620,532.10 and N29,402,608.90; and N33,002,661.70 and N149,413,255.00 respectively. The total loss to Lagos is N3,834,340,158,870 per annum (almost 4 trillion Naira!).

At 2.2km of road per 10,000 people in the megacity, Lagos already has one of the lowest road kilometre to people ratio in West Africa. The state also has 264 cars per kilometre as against 11 cars per kilometre world average. Having to contend with cargo traffic on the same roads has worsened the situation. The Lagos Masterplan includes seven rail lines but 21 years after its conception, the first two, the Blue and Red Lines are yet to be operational. The state government has said that the two lines will be ready by December 2022.

In September last year, President Buhari directed that all ongoing and future rail projects in Nigeria must be linked to the seaports. This is certainly good news but implementation could take decades. It is hoped that serious efforts will be made by government at all levels to develop railways to link businesses to markets (local and international) and that the Nigerian waterways are developed and become an option to move goods and passengers.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Wunmi

Nigeria should really look into building a modern national network of rails. The potential for economic development is just enormous. Nice read.