Possibilities from the changing climate for Nigeria

Nigeria faces two separate problems that are, in reality, connected. One is the slow-burning effects of climate change. Linked to that is the industrial transition currently underway from a reliance on fossil fuels towards cleaner, renewable energy sources like solar, wind and nuclear.

195 countries have committed to reducing their emissions of greenhouse gases. Improved technology has also made renewable energy sources like wind and solar cheaper. Heavy users of crude oil applications like the car industry will gradually move away from the resource. For example, Volkswagen, one of the largest manufacturers of motor vehicles in the world, has committed itself to carbon neutrality by 2050.

Global capital markets have also called time on companies unduly exposed to fossil fuels. BlackRock, one of the largest institutional investors in the world, has pledged itself to climate change-related metrics in its investing strategies. Green energy stocks now outperform fossil fuels stocks. That, in turn, informs the decision by oil majors like Shell and ExxonMobil to divest from expensive investments like Nigeria.

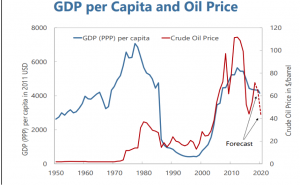

The economic threat to Nigeria from the slow but steady industrial energy transition is palpable and made visible during times of reduced oil prices. Since the 1970s, income from fossil fuels has been the Nigerian government’s primary revenue source. From 2010-2019, they were 93% of exports and 48% of government revenue. Oil and gas-related companies also accounted for 44-58 per cent of the revenue of publicly listed companies. Lending to oil companies comprised close to 40% of loan assets in Nigerian banks. That figure can only trend higher as foreign oil companies sell their assets to local operators. Those figures explain why recent economic growth has tracked increased crude oil prices (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: Source: IMF: 2020 Article IV Consultation, Page 6

Compounding the challenges facing the country from the knocks to its economic foundation and revenue base are the ill effects of a degrading environment.

Pollution in the Niger Delta has destroyed local ecosystems and economies. It has also fostered a long-running, simmering conflict between the State and non-State actors.

Sand excavation activities caused by increased construction during the country’s long oil boom and a poor understanding of the soil’s structure has turned soil erosion into a plague for the country’s south-east.

Across its pastoral and grain-producing Sahel regions, as of 2010, reports had the country losing 350,000 hectares yearly. Recurrent droughts and untamed floods have decimated livelihoods. They are also linked to a cycle of violence that has displaced millions.

That is not the full extent of ongoing environmental risks. Illegal logging and increased poaching activities pose not just environmental challenges, but could also seed more criminal elements challenging State authority.

Considering the important role played by crude oil exports to the broader Nigerian economy, it is possible that the structural changes being embarked on by the global community of nations to avert the threat of climate change will menace Nigerian prosperity. At the same time, the changing climate and a legacy of environmental degradation threatens its stability.

What is to be done?

Environmental degradation and economic development have often gone hand in glove. Nowhere is this clearer than the devastation wrought by bombs, diggers and human hands to get to the minerals that fuel the human economy. Anyone who has seen the picture of a mine can see that link between development and a scarred environment.

Yet there comes a moment when the tradeoff becomes impossible to sustain. When the mad dash must end and recuperation begin. William Blake, a British poet, first wrote of the polluting ‘dark satanic mills’ of industry in 1808. Yet, it was not until 1952, after as many as 12,000 people died from smog that the British government passed the first clean air act in the world.

China has been a byword for environmental pollution and the world’s largest polluter. Today, they are singing a new tune that ‘clear waters and green mountains are as valuable as gold and silver mountains.’ They pledge to be carbon neutral by 2060.

A new green economy is slowly emerging, blinking into the sun. Nigeria should endeavour to be a pioneering, active participant. That new economy will prove every bit as lucrative as the old one. In the USA, analysis shows that it was worth $1.3 trillion annually and employed 9.5 million workers as of 2015/16.

Nigeria can take advantage of this new emerging paradigm by tapping green financing. Those are structured financial activities used to encourage progression towards greening the economy. The market for global green bonds is expected to reach 2 trillion Euros by the end of 2023. In 2017 and 2019, the Federal government of Nigeria issued two series of green bonds worth around N25bn.

There is, however, another form of green financing that offers an alternative means of stemming the tide of environmental degradation in the country. They are carbon offsets.

A key aspect of the march towards a green economy is the achievement of carbon neutrality by fossil fuel users. Achieving carbon neutrality means reaching an equilibrium where an emitter ensures an equal amount of emissions and absorption. That is that their emissions are always, in the grand scheme, exactly zero.

There are two means of achieving carbon neutrality.

One is capture and storage. As its name indicates, it is a nascent technology whereby emissions are captured at the initial stage and either stored underground or chemically transformed into a non-pollutant. For example, water does not pollute. If carbon emissions could be transformed at scale into water, that would be carbon neutrality achieved.

Another means of attaining carbon neutrality is by offsetting. This is when emissions in one industry are offset by reduced emissions elsewhere. One way of reducing emissions is by making technology more efficient and by developing carbon sinks. Those are systems that capture more carbon than they emit. The natural carbon sinks of the world are soils, forests and oceans. According to estimates, they can remove 11 million gigatonnes of carbon.

That imbalance between emitters and carbon sinks has led to the emergence of a market in carbon offsets. In this market, emitters pay for the development of carbon sinks. In the case of Nigeria, that means that companies like Apple and Microsoft who have pledged to be carbon neutral by 2030 can help fund reforestation activities, the restoration of the marine ecosystem of the Niger Delta or the renewal of soil quality in the South-East.

The market in carbon offsets is not restricted to just those prominent companies, but emitters the world over. In other words, it can be lucrative not just to cut down trees but to keep them standing and plant even more.

British Petroleum is funding a project in Indonesia that offsets 19,149 tonnes of carbon dioxide yearly. It enables local households to process animal dung using biogas digesters. The environment sees reduced emissions from the unprocessed dung. Locals have access to cleaner energy from the biogas, and the waste derived from its processing leaves behind an organic fertilizer that precludes them from buying expensive chemical variants. They could even export their organic products abroad where the brand attracts a premium price.

It is estimated that the market in offsets trading could be worth as much as $200 billion by 2050. That makes it a potentially lucrative opportunity for the Nigerian private sector. Unlike petroleum and minerals, private sector growth leads to broader-based development.

As mentioned, environmental degradation is an existing reality in Nigeria. Nowhere does it loom larger than in the Niger Delta. Pollution in the region has been associated with reduced mangrove forest coverage, the destruction of the ecosystem, leading to reduced catches, and a poisoned water supply. Those effects stand at odds with aspects of the country’s sustainable development goals.

At present, the approach to rejuvenating the Niger Delta is a combination of government effort and exhortations of Multinational Companies. For example, the Federal government set up a fund in 2015 to begin the process of cleaning up the region. However, given existing revenue constraints, especially in the context of the continued transition away from fossil fuels, the Federal government may well struggle to complete the project. Relying on the oil companies to fund the clean-up is, at present, failing too. Recent reports indicate that only 11% of contaminated sites have seen work on decontamination start.

Similar attempts to commercialise gas flaring, in particular, through the Nigerian Gas Flare Commodification Programme have also faltered. In 2020, it is estimated that gas flaring in Nigeria emitted 19 million tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and cost Nigeria $1.24 billion worth of natural gas.

There can be another way. One which may well prove more effective, reduce government expenditure, draw in revenue and create a whole new sector for entrepreneurs to thrive in. It involves carbon pricing and embracing the world of carbon offsets.

The first step is to mandate a set price on carbon emissions. As we can see, those emissions have numerous negative externalities. Thus the logic for taxing them is the same as for taxing tobacco or gambling.

At the subnational level, state governments can set aside land for projects committed strictly to carbon offsetting and then inviting in foreign and local companies keen to achieve carbon neutrality by offsetting their emissions. Recent efforts to create a global market in carbon offsets should make this process easier.

State governments can also set up mini-emissions trading markets where high emitters like users of high capacity diesel generators or gas-guzzling jeeps can offset those emissions with a surcharge that goes into funding a cleaner energy source for the grid or developing waterways to aid less polluting, more efficient transportation. Current attempts in Shenzhen, China can serve as an example of such a process.

In all these, there exists a temptation to make this a government-led effort. It must be resisted. While efforts like the sale of carbon credits through the National Petroleum Investment Management Services are to be lauded. It should serve as an inkling of its potential not a vision of the future. Nigeria’s Green Economy must be private-sector led. Nigeria’s current debt-to-revenue ratio stands at 83%. That means that revenue from the Green Economy, if government-led, will primarily service debt. The private sector, in contrast, without those constraints can deliver projects with its customary efficiency.

Change is here. We must confront it. Nigeria cannot afford to ignore the potential of the Green economy. By embracing the Green New Economy, cheering on private sector participation and attracting foreign investment into the sector, we can prevail over environmental degradation.