In a post-pandemic world, Lagos must improve its connectivity

With the discovery, manufacture and distribution of various vaccines meant to prevent infection by the SARS-COV2 virus, humanity is slowly on the path to putting behind us the first great global shock of the 21st-century.

However, the threats from continued climate change still loom large. For example, Lagos and other low-lying parts of the country are threatened by rising sea levels. Further, the combination of drought, desertification and land degradation in Northern Nigeria has been linked to increased clashes between farmers and herders in the region.

Countries like Nigeria, with governments reliant on the extraction of fossil fuels, face a dual-threat. First from the economic stresses associated with the global economy’s shift towards a lower-carbon future, and second, from the weather anomalies linked to climate change. A glimmer of the economic threat of such an outcome can be glimpsed from the moment when a bout of panic at the height of the lockdowns associated with the pandemic led to oil cargoes in the US being traded at negative prices. Nigerian policymakers who grew up with a country whose problem, in the words of General Yakubu Gowon, was how to spend its money must realise that a future when crude oil is valueless is no longer fantastical. Indeed, it has already happened.

Those twin threats must focus minds towards starting, in earnest, to strategize towards a more prosperous Nigeria in a post-pandemic and post-fossil fuels era. The role of human capital and the development of cities could be the centrepiece of such a strategy. In Nigeria and indeed West Africa, no city looms larger than the centre of excellence, Lagos.

Lagos: The worst of both worlds?

Lagos is now a city of cities. With up to 6,000 people daily and 500,000 yearly moving to the city to seek opportunities, it does not lack for two things: people, literally (by 2100, it will have an estimated 88 million people), and enterprise. This combination of drive and mass has created the fifth largest economy in Africa.

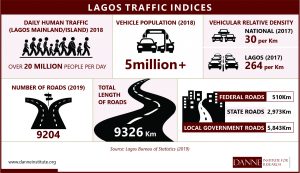

According to the Lagos Bureau of Statistics, the daily demand for trips in Lagos is about 20 million. Within the megacity, there are at least eleven cities with at least a population of 1 million. Its vehicular density is about 9 times greater than the national average. All these statistics attest to what already feels intuitive to Lagosians. It is, by far, the most densely populated city in Nigeria.

The diverse peoples within Lagos promises endless opportunities, and its density promises increased productivity. At first glance, it seduces: Lagos has Nigeria’s largest number of skilled workers and Abuja aside, is the country’s richest state on a per capita basis. On closer examination, however, it is disappointing. The Economist Intelligence Unit ranks it as one of the least liveable cities in the world. In the UN Habitat’s City Prosperity Index of 2015, it had a productivity score of 16.11. Lagos had the lowest score of the 11 African cities measured.

Lagos is the commercial and financial capital of Nigeria but also one of the poster children for gridlock in the world. It has a sizeable chunk of Nigeria’s human capital. This makes the current status-quo where Lagos is fragmented and congested a threat not just to the economic future of the state but the prosperity of the federation as a whole.

Lagosians are tired, poorer too, and poor connectivity is the issue

‘Traffic is a nightmare’ said Benson Onwuegbonu. It ‘drives you mad. You never get used to it’ said Marian Ikuenobe. Those are representative opinions from a ‘people’s voice’ segment in the Traffic and Transport Conference, organised by Danne Institute for Research and BusinessDay Media, held in Lagos in February. ‘Weak, tired, stress, fatigue’ were other keywords that ordinary people in Lagos used to voice the impact of the state’s current connectivity mishaps.

Commuting is far from cheap. Low-income residents spend 33 per cent of their budget on public transport, while middle and upper-income residents spend about 10 per cent according to the World Bank.

Lagos is a tale of two deficits: governance deficits during the military regime led to infrastructure deficits. In spite of increased expenditure on infrastructure by the Lagos State Government since 1999, the infrastructure gap is huge. According to Joseph Agunbiade, Co-founder of BudgIT, at current funding levels, it would take 27 years for Lagos to close its infrastructure gap. That makes innovation and private sector investment in Lagos absolutely necessary.

Lagos often markets itself as a large market due to its population. This is illusionary. The reality is that poor connectivity has fragmented what ought to be a unified single market, larger than many countries, into fragmented markets serviced by micro-businesses deterred by high costs and low productivity from expanding past the bus stops in their communities. It is no wonder that the megacity has a myriad of micro businesses which fail in the transition to small businesses.

The burdens placed on individuals are stark. For public transport users, traffic congestion represents out-of-pocket costs of N79,039 per annum. For private vehicle owners, the cost totals N133, 979. That is to say nothing of the productivity lost due to fatigued workers stuck in traffic for 2 to 4 hours, on occasion greater, every day.

Poor connectivity makes it difficult to link people to jobs, and businesses to labour and product markets. Those with jobs are endangered by the physical and mental stresses of their commute and businesses struggle to overcome logistic challenges and costs. Businesses in Lagos depending on their size stand to lose between N60,000 (for micro businesses), and N15 million (for medium sized businesses).

Lagos is Nigeria’s premier city. It is Nigeria’s gateway to the world and is a magnet for millions of entrepreneurial Nigerians. Reforms in connectivity are necessary for the state and its citizens to continue to thrive.

All roads lead to Productivity through Connectivity

The traffic congestion problem has to be fixed if Lagos is to become a productive and prosperous city. On the demand side, we suggest the transition to remote work, flexible resumption times, employee reassignment closer to where they live and the development of alternate economic centres in the mini-cities within Lagos megacity. However, remote work or working from home is reliant on stable power supply and Internet connectivity. For the most part, this is still a challenge in Lagos. Besides, not every job can be moved online. Regardless, investment commitments for faster internet is key.

On the supply side, the need for a multi-modal transport system cannot be overemphasized. The Lagos rail project is long overdue. The heavy reliance on roads despite their small size and limited numbers compared to the demand for trips is unsustainable. The roads are overwhelmed. There is also a need to develop water transportation. We must get people off the Danfos and private vehicles into mass transit rails and ferries. It is not enough to maintain roads and build drainage systems. If Lagos is to work, the over reliance on the road network must stop.

What has been said here about Lagos applies to other parts of Nigeria. In states with infrastructure deficits, the choice of which infrastructure project to undertake can make a difference for economic growth and reduction of poverty. Improved connectivity can open up a community, attract businesses and improve livelihoods.

Improved connectivity was used to reduce poverty among the people of some communities in Anambra State. In an interview published in the Handbook of Organizational Change in Africa, Governor Peter Obi said, “Because fighting hunger was our first goal, poverty mapping helped us identify the poorest areas in Anambra State. We saw that the poorest area of Anambra was Anambra West Local Government – Ogbaru and Orumba South. Once we had located the poorest people, we asked why they are poor. We discovered that their problem was lack of accessibility, road network. These communities were agricultural communities with no access to market where they could get more value for their products; they were selling far below market price. Our road construction projects began in these communities. When the roads were completed, we saw a reduction in poverty of the people: yam tubers which used to sell for close to nothing now attracted five to ten times the price.”

Connectivity opens up communities for business and improves livelihoods. It can be used strategically to drive economic growth. A well-connected city is a prosperous city. A city that works is a city with high productivity. That requires mass connectivity.

To confront its imminent challenges, Nigeria needs her people united. There is no better first step than getting them connected. Nigerians must be able to truck and barter at scale without friction. On land, on air, by sea or waterways and in the internet cloud. Improving the connectivity challenges that currently blight the country is a task that must be done.